The Company: Looting the Jewel in the Kedah Crown

WHAT follows is the story of Kedah, as much as the story of India. Visiting the Indian forts in Agra and Jaipur many years ago makes one wonder of what had gone missing. The splendor of the 15th/16th century Indian forts dwarf European castles. Indian architecture, design and function of space, and its artefacts – daily objects and what we would see as exotic displays, were once symbols of power and civilization.

The structures are now hollowed. The tour guides there would say that the English took it back – they looted. One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: “loot”. The Oxford English Dictionary, wrote the word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late 18th century. It suddenly became a common term across Britain.

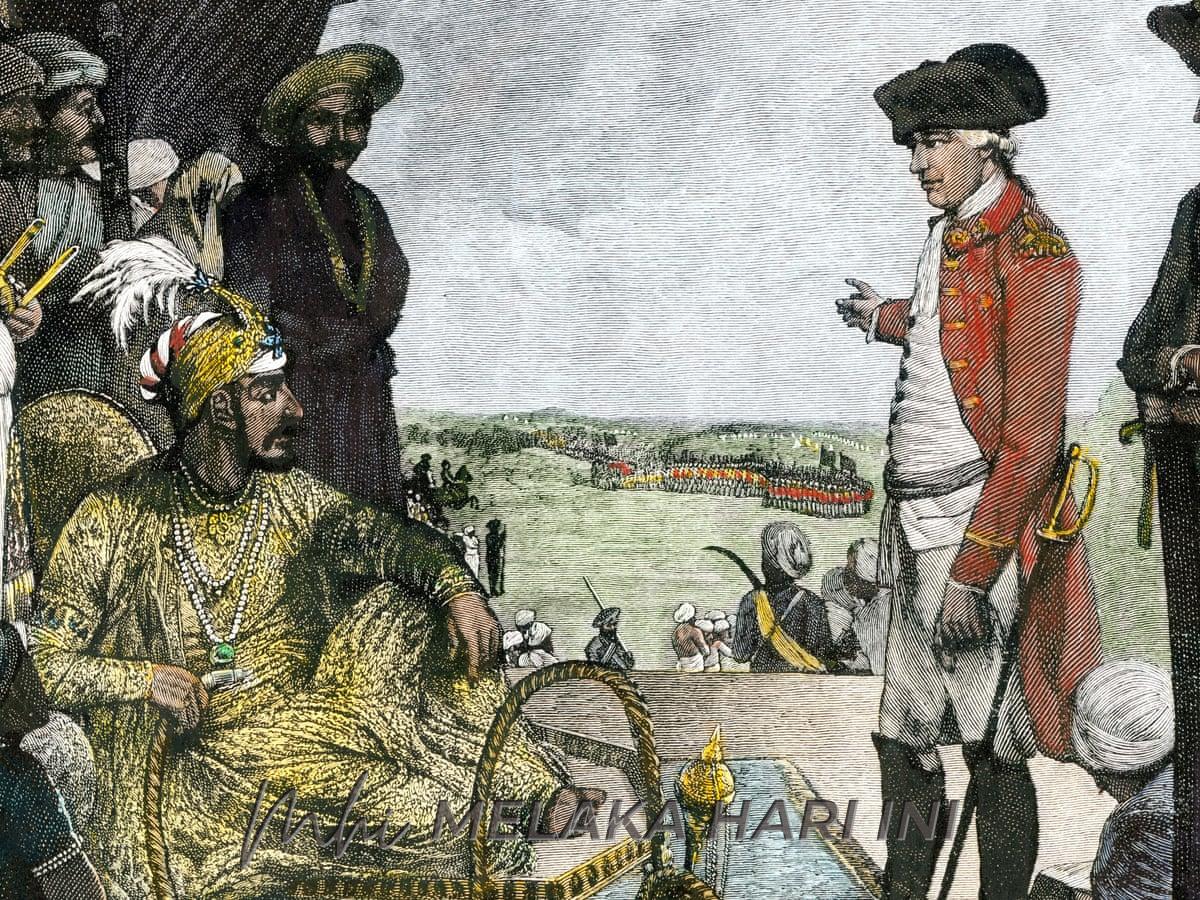

Writer and historian William Dalrymple argued that the EIC conquered, subjugated and plundered vast tracts of south Asia (and of course of the Malay Peninsular, and Borneo, and what would have been Sumatra and Java, if not for the Dutch) – “The lessons of its brutal reign have never been more relevant.” Dalrymple described what he saw of a scene from a painting in August of 1765, six years before the theft of the Kedah island. The painting shows a scene when the young Mughal emperor Shah Alam, exiled from Delhi and defeated by EIC troops, was forced into what we would now call an act of involuntary privatization, by the “the high and mighty, the noblest of exalted nobles, the chief of illustrious warriors, our faithful servants and sincere well-wishers, worthy of our royal favours, the English Company”. Mughal taxes was subcontracted to the pirates in disguise.

Dalrymple in “The East India Company: The Original Corporate Raiders,” published in The Guardian (2015), told us that 250 company clerks backed by the military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers had become the effective rulers of Bengal – the aggression of colonial power.

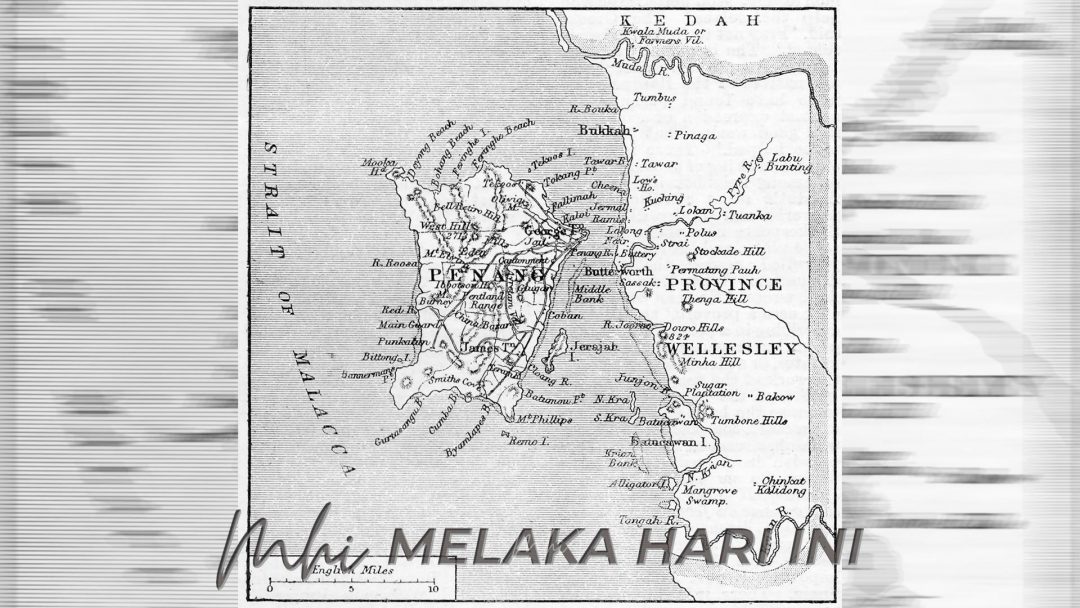

There goes Bengal in 1756, 20 years later it was Pulau Pinang; and 47 years later, extending to the Mughal capital of Delhi, and almost all of India south of that city was by then effectively ruled from a boardroom in the City of London. “What honour is left to us?” asked a Mughal official named Narayan Singh, shortly after 1765, “when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?” In 1874, the gates were opened for the rest of the Malay peninsula.

We were reminded that it was not the British government that seized India, or the island off the coast of Kedah at the end of the 18th century. It was a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London. It was managed in India by an unstable sociopath – Robert Clive.

We may remember the Battle of Plassey in 1757 to pass our history exams. According to Dalrymple, it was victory that owed more to treachery, forged contracts, and bribes. Clive transferred to the EIC treasury no less than £2.5m seized from the defeated rulers of Bengal. In 1771, the Kedah island was earmarked. It was to be an illegal occupation. There was no treaty. Nevertheless illegal, even with a treaty.

Dalrymple’s description on the opening of British rule in India resonated the EIC in the Malay Archipelago. At the height of the Victorian period – although Light and the EIC adventures took place during the Georgian era – there was a strong sense of embarrassment about the shady mercantile way the British had founded the Raj. The Victorians liked to think of the empire as a mission civilisatrice: a benign national transfer of knowledge, railways and the arts of civilisation from west to east. There was a calculated and deliberate amnesia about the corporate looting that opened British rule in India.

In its charter in 1600, the year the company was founded, no mention was made of the EIC holding overseas territory, but it did give the company the right “to wage war where necessary.” The Company was to become “an empire within an empire,” as Dalrymple noted. The state later bailed out the pirates, history’s first mega-bailout supported by the British parliament. Parliament backed the company, gave it state power, ships, soldiers and guns.

In England, the EIC has bought off parliamentary opposition by donating £400,000 to the Crown in return for its continued right to govern Bengal. Warren Hastings, of which Light made many dealings for Pulau Pinang was brought to court and went on trial for looting and corruption in 1788.

The EIC recruited retired politicians, remarked Dalrymple. The man whose name has given fame to Fort Conwallis – the former Tanjong Penaga that Light had landed on 20 August 1786, was one such example of the recruitment. Lord Cornwallis, who oversaw the loss of the American colonies to Washington, was recruited by the EIC to overseas its Indian territories. It was ‘corporate greed’, as Dalrymple described of the EIC. The British state has to tame “history’s most voracious corporation.”

The company’s shareholders have purportedly become that of the State – “a state in the guise of a merchant. Citing what was to be the book titled Anarchy in 2019, Dalrymple in retrospect reflected that the rise of the Company seems almost inevitable. But that was not how it looked in 1599, “for at its founding few enterprises could have seemed less sure of success.”

Then, England was relatively impoverished, having spent a century at war with itself over the most divisive subject of the time: religion. England therefore had unilaterally cut themselves off from Europe – a kind of early “Brexit.” To Europe then, England had turned into something of a pariah nation, which stole the Jewel in the Crown.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.