Singapura 19th Century Malay Protest: The News in the Syair Tantangan

The Malay syair is a valuable historical source. Compared to the hikayat, genealogies and other traditional prose forms, the syair is more actual in its narration, chronicling what is empirically observable. These can be seen in such compositions as Syair Perang Aceh, Syair Maulana, and Syair Raja Kecil Di Siak. There is also Syair Mokumoku from Bangkahulu, Sumatera, Syair Pangeran Syarif, chronicling life in the 1890s in Pontianak, Kalimantan, and Syair Duka Nestapa, a Kedah syair written by Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin II during his exile in Melaka between 1822-1841.

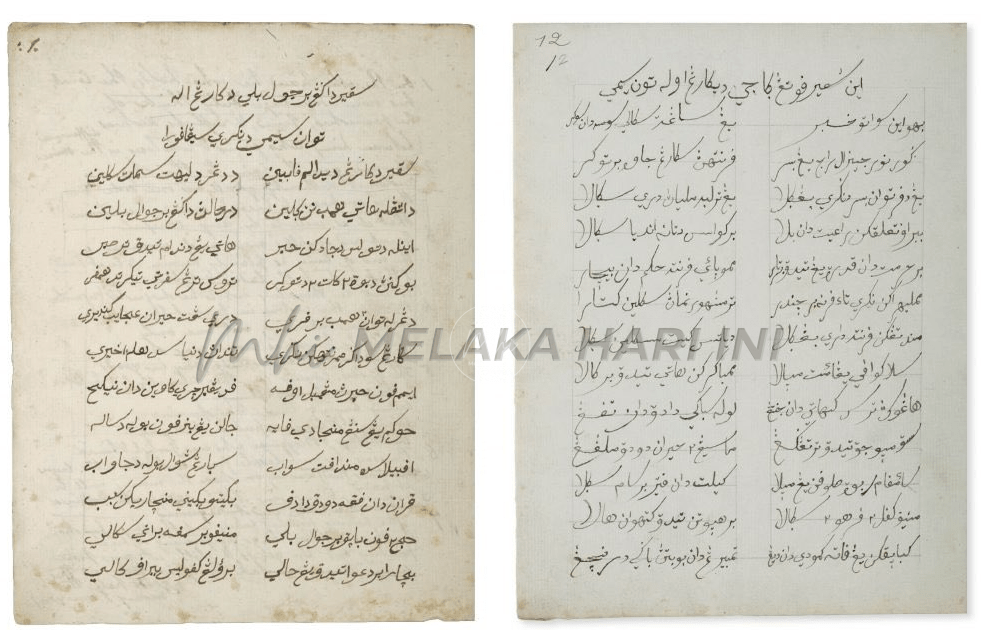

These focus on people and events, much like Abdullah Munshi’s Syair Kampung Gelam Terbakar (1847). The Syair covers an actual event that happened, which we today would define as news. There is another set of news genre written in that form, discovered at the National Library in Paris in 1986. There are three syairs grouped under one title called Syair Tantangan Singapura Abad Kesembilan Belas (Protest Syair about Singapura in the 19th century).

The Malay word “tantangan” has three meanings: “protest” (from the Bahasa Melayu root “tantang”), “challenge” (also from the word “tantang”) and “concerning about” (from the word “tentang”). The syair demonstrates the author’s displeasure at events in Singapura. Historian Badriyah Haji Salleh (2007) in her article “Syair as a Historical Source: The Syair Tantangan Singapura, a nineteenth century text,” identifies the syair as some of the earliest forms of protest. The first two were directed at British and traders, and the third was at the family of Sultan Hussein Muhammad Shah, the sultan of Singapura installed by Stamford Raffles.

National Laureate Professor Muhamad Haji Salleh describes them as “dark” syair “since they contain messages of discontent,” which was uncommon for anyone within Malay society. He deems the Malays as “too polite” to protest openly. Complaints were presented. In classical Malay texts, we find these in allegories and satires. It was argued that the direct nature of the expression could be one of the reasons why such “dark” syairs “were not circulated widely.” But who determines or decides their circulation? Was it not the colonial authorities of the day?

The description of these as “dark” syair is erroneous; and Eurocentric. It is “dark” from the colonial perspective. It is also incorrect to assume that these are periods of “transition.” Transition from what to what? If there were already narratives of discontent in earlier 16th and 17th centuries Malay texts, why would this be “the beginning of an era?”

The Syair Tantangan was written in 1833, four years earlier than Abdulah’s Hikayat Pelayaran Abdullah. The first syair under the collection of Syair Tantangan is titled “Syair Dagang Berjual Beli Dikarang oleh Tuan Simi di Negeri Singapura” (Syair on Trading Composed by Tuan Simi in the Country of Singapore). Simi, also written as Siami, is a little known personality in Malay literary history. He was first employed as a Malay writer for Raffles in Pulau Pinang in 1805, and later was appointed customs official by the East India Company in Singapura . Ian Proudfoot in a 2007 JMBRAS article titled “Abdullah vs Siami: Early Malay Verdicts on British Justice” states that Siami was retrenched in 1830.

The syair comprises 56 stanzas. The environment in Singapura at that time was “alarming and disturbing.” And so, Siami penned his thoughts and feelings in the form popular at that time, that is, the syair. He chronicles what he saw, knew and experienced, beginning with

Syair dikarang di dalam pabean

Didengar dilihat semata sekalian

(The syair is composed on the verandah

To be heard and see by all and sundry)

To Badriyah and Muhammad, the syair is seen as a historical source – historical from the present perspective. The source of the past from the present tense. Another way to evaluate the syair is that it represents an individual’s anxiety and anger about the changes around him under British rule. To Siami, the changes had dislocated Malay society. He highlighted several issues such as deteriorating social and moral values, corruption, fraudulent trading, communal conflicts and injustices. Yet another way to view the syair is its coverage of an event, what we call news. It is a literary expression of reality. In another stanza, Siami wrote:

Imam pun khabarnya mengambil upah

Pada yang bercerai kahwin dan nikah

Hukum yang senang menjadi payah

Jalan yang benar pun boleh disalah

(It is said even the imam imposes charges

Upon divorce, marriage and betrothal

Making simple laws difficult

The right path wrong)

In Syair Potong Gaji Dikarang oleh Tuan Simi (Syair Wage Cut Composed by Tuan Simi), the author voices his anger and frustration toward the British administration and the EIC. Siami was concerned about his community. He described his anger as thus:

Mendatangkan perintah dari Benggala

Di atas kita sekelian segala

Selaku api yang amat menyala

Membakarkan hati yang tidak berkala

(Came a directive from Bengal

Upon everyone of us

As fire that is blazing strongly

Burning the hearts without occasion)

He saw the Malays in Singapura facing turmoil and hardship. He used the imagery of “ribut taufan” (storm), “kilat” (lightning) and “petir” (thunder); and described the turmoil as “meniup kapal-kapal perahu segala” (blowing ships and all craft helter-skelter). The waters and the seas are part of Siami’s ensemble in his plea for the Malays to fight. The “kemudi” (rudders) and “dayung” (oars) were threatened by the colonial economy. If the Malays do not protest, then they would be left to the mercy of the waves.

#####

Next title:

Ali Wallace of the Malay Archipelago

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.