Saudara (1928-1941): Covering Melayu Tanjong and the World

Saudara (Brother) was a Tanjong-based international newspaper before the Second World War. The newspaper had readers throughout the Malay states, Siam, Sabah, Sarawak, Indochina, Kalimantan, the islands of Jawa, Sumatera, Sulawesi and Labuan. It was also read in Eqypt, the Hijaz and London. (Saudara 7 June 1930).

Its correspondence and news networks were global, coming from places like Eqypt, Afghanistan, Russia, Makkah and the Malay states. Saudara’s correspondents used the telegraph and cable.

Saudara was another vehicle for Sayyid Shaykh Ahmad al-Hadi. It was two years after starting Al-Ikhwan in 1926. Al-Hadi recognized the force of the changes that were taking place then. From al-Imam (1906), and a few others in between, he turned to a more secular paper. Saudara nevertheless, expressed significantly enough the same idea as that contained in Al-Ikhwan. Pendeta Za’ba in 1941 had described Saudara as one of the most influential newspapers in Malaya and an uncompromising critic of Malay life.

Saudara carried the slogan “Majulah ke Hadapan Wahai Saudara: Warta Am, Pelajaran, Pengetahuan, Perkhabaran” (Move Forward, O My Friend: General News, Education, Information, Message). Among its permanent features were “Pengetahuan Am” (General Knowledge), “Perkhabaran Alam Dunia” (News of the World), “Berita-berita” (News), “Warta Tanah Arab” (Arab News), “Warta Indonesia” (Indonesian News), “Buah Fikiran,” (Thought), “Warta Benua Eropah” (News from the European Continent), “Perkhabaran Mahkamah” (Message from the Court), “Warta Negeri Siam” (News from the land of Siam); “Perkhabaran Alam Melayu” (News from the Malay World), and “Surat Kiriman” (Letters to the Editor).

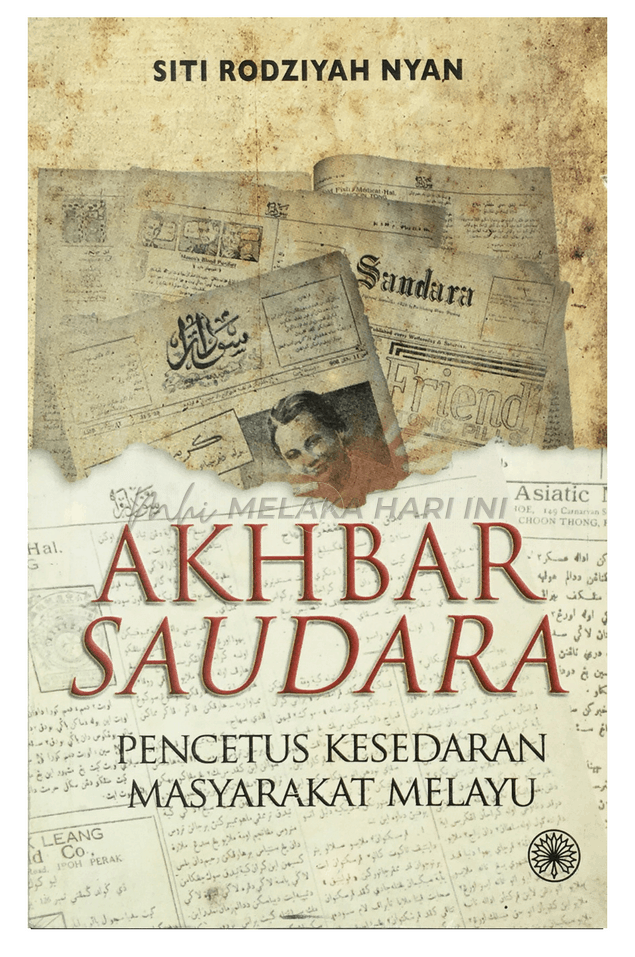

Siti Rodziyah Nyan (2009) in Akhbar Saudara: Pencetus Kesedaran Masyarakat Melayu, discusses at length the contents and context of one of the major Malay newspapers in the period. Popularly accepted as a ‘national’ newspaper, Saudara played a major role in boldly mobilizing Malay society toward economic and social advancement.

Al-Hadi exercised considerable editorial influence over the newspaper until his death in 1934. Printed at the Jelutong Press until 1939, the paper changed hands managerially when the press was sold at that time. From 1928, it was published by his son, Sayyid Alwi Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi. Publishers for the remaining two years from 1939 were listed, successively, as Raja Othman Mohd Noor, S.A.O. Alsagoff, Shaykh Abdul Rahman Abu Bakar, and Mohd. Che’ Ambi.

William Roff (1972) listed Saudara’s editors as Mohd. Yunus Abdul Hamid, 1928-31; Sayyid Alwi Sayyid Shaykh al-Hadi, 1930 – February 1933, March 1934 – mid 1936; Sayyid Shaykh Ahmad al-Hadi, Feb 1933 – Feb 1934 (died); Abdul Wahab Abdullah, Feb 1933 – Mar 1934; Shaykh Mohd. Tahir Jalaluddin, Mar – Sept 1934; Abdul Majid Sabil, mid 1936 – June 1939; and Mohd. Amin Nayan, late 1939 – 1941.

When al-Hadi took over the editorship from his son Sayyed Alwi in 1933, he was assisted by Abdul Wahab Abdullah. According to Siti Rodziyah, Abdul Wahab was from Chemor, Perak, and was educated in Eqypt. He was what we can describe as a polymath, conversant in such fields as earth sciences, surveying, chemistry, botany, music and painting. He was able to speak English, Arabic and French. Abdul Wahab was educated at the Madrasah al-Mashoor in Tanjong and was taught by al-Hadi.

Having an editor with such a background and skill was certainly instrumental in displaying the character of a newspaper, and its response to the mood and issues of the day. And Saudara certainly had the advantage of having another member of the Malay intelligentsia, this time an ulama in Syeikh Tahir Jalaluddin who took over as editor in March of 1934. The decade of the 1930s saw a heightened consciousness in Malay nationalistic sentiments (the semangat kebangsaan Melayu). This attitude was induced by migrants questioning the position of the Malays in the Malay States and the Straits Settlements. Saudara’s leaders and editorial comments were much reflective of the spirit of the times.

In a response and in increasing the space for Malay expression, Saudara created a column specifically to cater for readers opinions and comments. Named as Halaman Kanak-Kanak (Childrens’ Column), it was organized by Ahmad Khatib. The column, despite its name, was certainly not for children. It was perhaps conceived as such due to the nascent political consciousness amongst the Malays then. It was also suggested that Saudara had wanted to educate young Malays to be nationalists, and mujtahids (authority in interpreting law and doctrine) echoing the reform movement much earlier in the century.

Later in the same year, on 3 October, the column was amended to Halaman Sahabat Pena (Pen Pal Column), providing space for opinions and the exchange of thoughts and ideas. On this, Saudara commented in its 3 October 1934 issue that Halaman Sahabat Pena was to accommodate writings and essays from Malay youths. The Halaman Sahabat Pena later gave birth to the Persaudaraan Sahabat Pena Malaya (Paspam). Paspam, for the first time, became a medium for Malay unity. It united the ‘semangat Melayu’ of the peninsular in expressing modernist religious views.

One thousand copies of Saudara was printed per day in 1928. Its circulation increased to 1,500 to 1700 in 1929. In 1930, its circulation declined to 1400 copies, only to stabilize at 1500 in 1931 through 1935. That figure was considered one of the biggest print run for a Bahasa Melsyu newspaper in Pulau Pinang before the War.

According to Mohd. Hamedi Adnan (2015), with the size of 15.5 inches x 21.6 inches, it has the largest format among Bahasa Melayu newspapers. It grew from a four-paged newspaper to an eight-paged one toward the end of 1928. Eventually Saudara became 12-page newspaper by the end of the 1930s.

Saudara was published weekly every Saturday until January 1932 when its frequency was twice a week (every Wednesday and Saturday). It was sold for 10 sen per copy with an annual subscription rate of RM10.00. Beginning 1930, its advertising rate was 50 sen per inch, up from 25 sen earlier. Among the advertisements it carried were cigarettes. One was the label ‘Gold Sports’ with a drawing of a woman smoking. Readers of the Kaum Muda organ protested. That image was later replaced by that of a man.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.