Revisiting Melaka as Global History

PROF. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican

THE emergence of recent voices calling for decolonizing names and narratives in Malaysia cannot deny the history of colonialism in this part of the world. The story of the coming of Europeans to Melaka and the Malay Archipelago serves as integral to our history.

The shores of Melaka, and that of other ports in the Malay Archipelago, emit a cacophony of sounds from all over the world. Yet, the history of Melaka has not been essentialized in that sense as integral to the global narrative. The Muslim Sultanate of Melaka signifies a globalized history and civilization. My initial thoughts on this was linked to Panglima Awang.

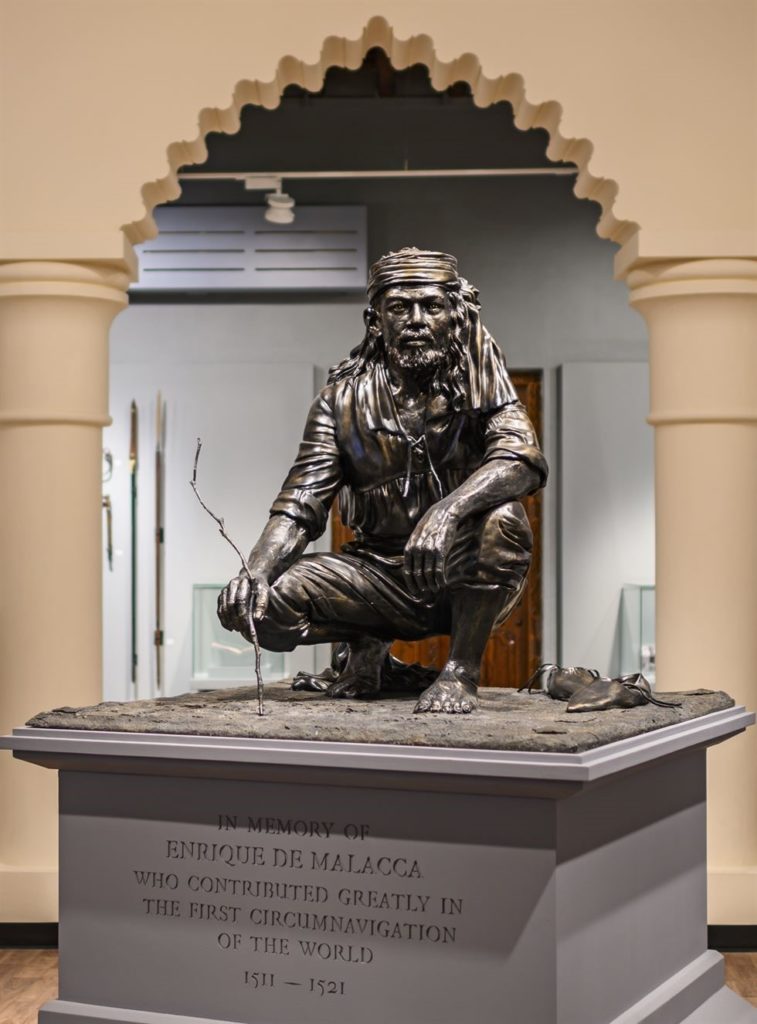

In a talk titled titled “Panglima Awang@Enrique de Malacca: Melaka, Globalization and Malay Civilization” given last year in Kuala Lumpur, I suggested for a re-understanding of Melaka’s past, and hinted at the use of history for the present and the future. The trigger was Harun Aminurrashid’s 1958 historical novel Panglima Awang.

Harun based his story on the persona of Enrique de Malacca, captured by Ferdinand Magellan in Malacca in 1511, and served as interpreter and navigator for the Portuguese in circumnavigating the globe. While the first person to sail around the world will mostly still be disputed for years to come, the story of Panglima Awang, the name given by Harun, is the story of Melaka, and its links with Europe. That train of thought led me to Bahasa Melayu as lingua franca spoken in Melaka and the Malay Archipelago. How else would more than 84 languages and ethnicities be managed in the port city of Melaka?

And the Enlightenment of the Melaka Malay Sultanate must be seen against conditions Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. There is a lacuna on writings of the history of Melaka being entwined with Europe, and vice versa, even Melaka history as part of Asian connections.

The history of Europe, hangs on to the history of Melaka — citing historian Tome Pires’ famous words: “Whoever is lord of Malacca shall have his hands on the throat of Venice”.

The history of Melaka corresponds to that of medieval Europe (to use the Eurocentric periodisation) — especially Portugal and Spain. A phase of Enlightenment in the Tanah Air began much earlier than the European Enlightenment (of the French philosophes) in the 18th century.

The year 1511 is not disconnected to the Treaty of Tordesillas on June 7, 1494. That treaty dragged Melaka into the disputes and rivalries at the far end of Asian landmass that we now call Europe. The fate of Melaka was sealed when the Portuguese broke through the back door into the Indian Ocean in 1498 and disrupted the order of civilization of its polities, and maritime regulations which have their genesis centuries earlier.

The Portuguese monopoly intervened into the litorral societies generated by the harmony in trade, and cultural exchanges from the coast of east Africa to the eastermost corner of the Malay Archipelago. It opened up what Indian historian and Diplomat, K.M. Panikar dubbed as “the da Gama epoch.” And thus began what is aptly titled by Panikkar in his 1953 classic as Asia and Western Dominance.

The Treaty was initially to resolve over what began in 1492 when Christopher Columbus first sailed across the Atlantic Ocean. Between the Portuguese and the Spaniard, conflicts had to be settled over lands newly “discovered or explored” by Christopher Columbus and by other late 15th century European voyagers. The treaty signed at the town of Tordesillas in Spain, saw the two kingdoms dividing the world into themselves. The world was divided into two equal hemispheres between Portugal and essentially Catalan then – the eastern half would be part of the Portuguese domain, and the western half that of the Spanish. Their vessels could only navigate in their own spheres. The Treaty was arguably narrated as a “diplomatic agreement” about territorial division “that indeed did not raise questions of evangelization.”

Hence the rivalry carved out the monopoly over navigation, trade and discovery. It gave the Ferringhi more claims over most of the Indian Ocean. The divisions later became known as the doctrine of discovery. It gave Europeans the “legal right” to discover all lands occupied by non-Christian peoples, the “Saracens or pagans”, merely by setting foot on it. We see this disguised as a colonial demarcation.

A dispute in the monopoly of cloves in the Maluku islands in about 1510, was later finally resolved by the Treaty of Saragossa on 22 April, 1529, practically determining the anti-meridian corresponding to that of Tordesillas. But that was not the end. The monopoly created by Tordesillas in favour of the Iberian powers was later challenged by France, England, and the Dutch. Redeeming Melaka as European and global history is another challenge.

**Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican is Professor of Social and Intellectual History with the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, International Islamic University (ISTAC-IIUM). He is a Senior Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research Centre and Hub at De La Salle University, Manila, the Philippines.