Religious Periodicals in Malaya: Pengasoh, The Modern Light and Similar Genres

In a few of my previous columns, I mentioned the monthly al-Imam (1906-08). Regarded as “the first radical Malay newspaper”, Al-Imam embodied the spirit of Syed Shaikh al-Hadi and its other founders. The periodical was a landmark in the history of Bahasa Melayu journalism in Malaysia.

One category of periodicals in Malaya can be described as religious in nature. These are either wholly or largely concerned with the religion of Islam – either in perspective, or prescriptive. In the history of Malay journalism in Malaya, the manifestation of Islam can be gleaned in various ways. Apart from Bahasa Melayu periodicals, there were also English-language ones devoted to Islam in their coverage of news and opinion.

Historian W. R. Roff (1972) in his study of Malay newspapers and journalism before the Second World War describes the situation as “few journals, even the more frivolous, did not devote some space to discussion on Islamic matters.” He estimates that there were some two dozen Bahasa Melayu periodicals appearing between 1916 and 1941 under the category. Out of this, six were in English. He divides this into three groups: general Islamic periodicals, those associated with educational institutions (mainly madrasah), and those associated with other sorts of religious institutions (mainly clubs and societies).

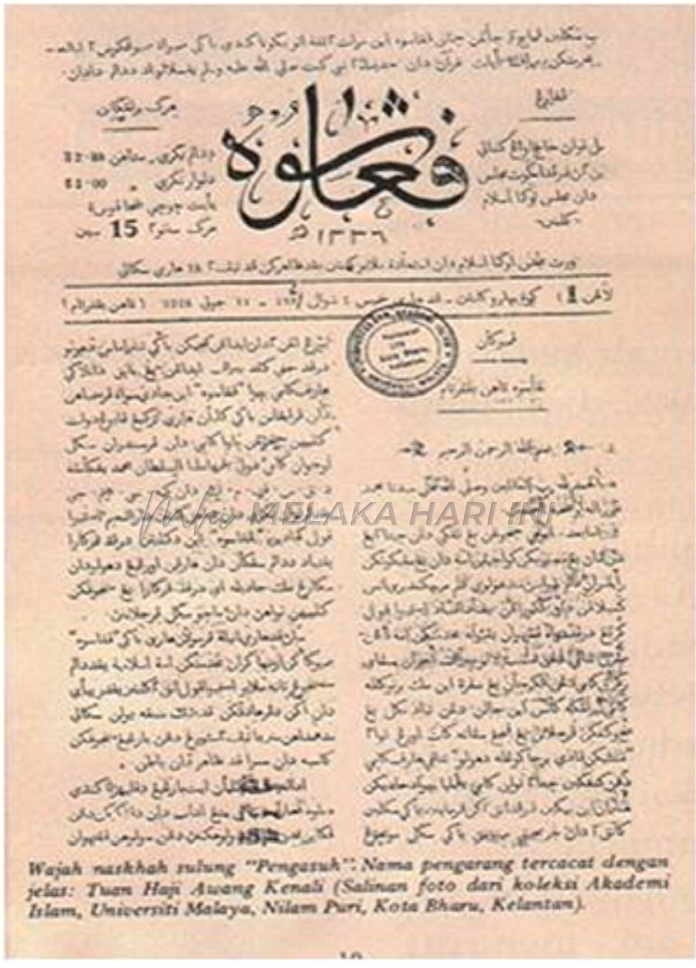

Bearing in mind the earlier periodicals such as al-Imam in the first decade of the 1900, another periodical made its appearance in 1917. This was Pengasoh, emanating from the Majlis Ugama Islam Kelantan, set up under the authority of the sultan. According to Roff, Pengasoh, which appeared fortnightly until 1932, and then weekly, “became in its own way one of the leading intellectual journals of the time, addressing itself to practical Islamic matters and related social and economic questions of contemporary concern.” He remarks that Pengasoh is the first periodical of any consequence to be published outside the Straits Settlements.

Based in Kota Bahru, Kelantan, it rendered a cosmopolitan outlook, widely circulated throughout Malaya. Pengasoh, not manifestly reformist, nor displaying any doctrinaire persuasion, in the nature of al-Imam, was contributed by most of the leading Malay writers of the period. A notable contributor was pendeta Za’ba. It was often seen to be innovative in ideas. It was thought to have ceased publication at the end of 1937. It is still published to this day, in a different form.

Al-Ikhwan and Saudara were two Pulau Pinang based periodicals of the similar genre. The former appeared in September 1926 under al-Hadi. Al-Ikhwan lasting a little over five years, was essentally an Islamic journal with a reformist purpose. The periodical was a social and even a political campaigner covering diverse subjects, from the emancipation of women to the provision of more English education for Malays. Two years later, it was joined by the weekly Saudara. Both from al-Hadi’s Jelutong Press, played a crucial role in revitalizing Malay society.

Also from Pulau Pinang was Semangat Islam. Lasting for about 18 months, the periodical edited by Abdul Latif Hamidi espoused “a fairly politicized kind of reformism.” Students from Al-Azhar in Cairo were frequent contributors.

Apart from general Islamic periodicals, there were also monthly periodicals by religious educational institutions. These were mainly short-lived. The following includes Al-Raja(1925-6), of Madrasah al-Mashhur (al-Mashoor), Pulau Pinang; Jasa (1927-31), Madrasah al-Attas, Johor Bahru; Temasek (1930), Madrasah al-Juneid, Singapura; Suara (1931), Sharikat al-Ittihad al-Islamiah Kota Bahru; Panduan (1934-5), Madrasah al-Idrisiah, Kuala Kangsar; and Seruan Ihya (1941), Madrasah al-Ihya Abu Sharif, Gunong Semanggol, Perak.

There was also Lidah Teruna, a fornightly paper between 1920 and 1921 by the Persekutuan Perbahathan Orang2 Islam of Muar. In 1926-7, the Persekutuan Guru2 Islam, Muar, brought out a monthly call Lembaran Guru.

Less known are the English-language periodicals devoted to Islamic matters. Roff identifies a total of six of such periodicals “either because Malays were in some ways associated with their production or because they were known to have circulated among the English-educated.” Only one, notes Roff, was in all senses wholly Malay. This is The Modern Light. Founded and edited in Johor Bahru in May 1940 by Haji Abdul Majid b. Zainuddin and his son, Haji Abdul Latiph, The Modern Light described itself as “the only Malay national organ in English.” Haji Abdul Majid is previously with the Malayan Pilgrimage Officer and British Vice-Consul in Jeddah.

Eighteen monthly issues of The Modern Light were published fortnightly. Its articles were often polemical “of a patriotic kind informed by a lively Islamic spirit and some Islamic knowledge.” The remaining five English-language monthlies, were all published in Singapura. The Muslim (1922-5) by the Anjuman-i-Islam in conjunction with the Woking Muslim Mission, comprising articles reprinted from the Islamic Review. It was somewhat associated with the Lahore Branch of the Ahmadiyya movement. Real Islam (1928-30), with at least one Malay in the editorial board, espoused views that were markedly anti-Ahmadiyya.

There was also Genuine Islam (1936-41). This was the journal of the All-Malaya Muslim Missionary Society. The Muslim Messenger, which appeared in 1936, seemed to have been editorially Malay and was presumably missionary in intent, notes Roff. The Voice of Islam (1937-9), was also anti-Ahmadiyya in emphasis. Described as “Indian in inspiration” the periodical appeared under the local patronage of Tengku Temenggong Ahmad of Johor.

Of these, we can find only Pengasoh. The Kota Bahru-based periodical is able to sustain itself, continuing the intellectual tradition, albeit in a different form and spirit.

#####

Next week:

The World View of Harun Aminurrashid, Creator of Panglima Awang

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.