Maps, Renderings, Images: The Malay World before Photography

EQYPTIAN / Greek astronomer, mathematician and geographer, Claudius Ptolemy calls the Malay Peninsula the Chersonesus Aurea (‘The Golden Peninsula’). The Indians refer to it as the Land of Gold. The oldest surviving map of the Peninsula is the 13th century Geographike Huphegesis (‘Guide to Geography’) based on data collected by Ptolemy in the 1st century. The Geography, also known by its Latin names as the Geographia and the Cosmographia, is a gazetteer, an atlas and a treatise on cartography.

Ptolemy has enabled us to ‘see’ a trading system, between the East and the West through the Malay Peninsula route in the 1st century. Ptolemy’s records have made possible the Sungai Batu excavations. Stone inscriptions, coins, archaeological artifacts have added to the pictorial evidence of Malaysia.

The earliest modern map of Malaya and Sumatra is by Martin Waldseemuller (1470-1518) in 1513. There is a woodcut, edited by Michael Servetus. Printed in Lyon, France in 1535, it featured trading posts on an oddly shaped peninsula that would persist on other European maps until the arrival of the Ferringhi.

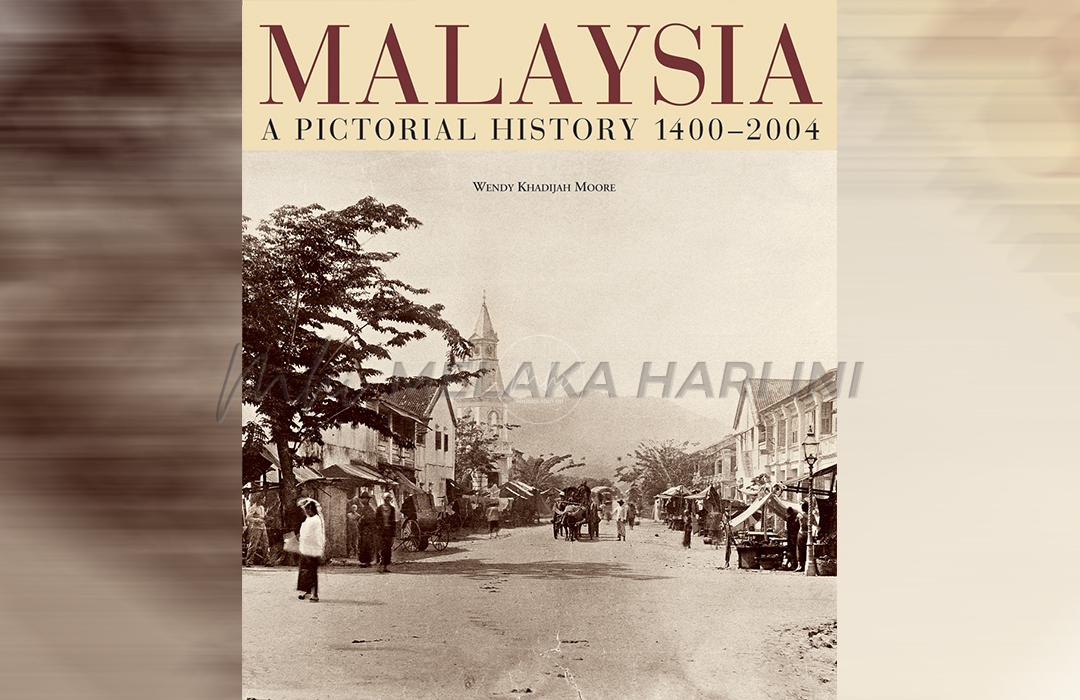

There were local maps indigenous to the Malay Archipelago. The Portuguese had apparently used Javanese charts. The charts showed Brazil and Portugal. In her landmark book, Wendy Khadijah Moore (2004) introduces us to Malaysia: A Pictorial History 1400 -2004. As the nation celebrates her 64th year, we wonder how our past looked like. The book presents a visual history of Malaysia.

She argues that a history in pictures has its limitations and its bias, created by the painter or photographer. Before the invention of photography in 1839, artists could easily eliminate whatever they did not want in their sketch or water color; while other elements are improved upon, or even invented. Imagination had a more important role than factual representation in the very first images of Malaysia.

Chapter 1 of the book is titled “The Malay World 1400 – 1849.” The author begins by rendering the image of Melaka. Describing the Melaka Sultanate as the paragon of Malay culture and success, she brings us to imagine “of the palace with its seven-tiered copper roof, its mirrored walls and gilded doors, or of the players – the bejewelled sultans with their supernatural aura, the court with all its intrigues, the traders, artisans, scholars, and missionaries who created the 15th century empire…” Engravings from the 1600s capture the Malay courts.

One is titled “Carosse Royal de trente roues tire par douze Elephans” showing a royal party in an unusual canopied carriage pulled by a dozen elephants (see page 23 of the book). We do not know which Malay court the engraving depicts; and most likely from a description rather than a personal experience, as Moore describes on the many engravings of the day. She suggests that the party may be that of Admiral Pieter Willemszoon Verhoeff, on his way to the Johor court “to participate in a joyous celebration at the end of Ramadan in 1608.”

Two importance written sources, commonly used by scholars on the Melaka Sultanate a century after its demise were the prose masterpiece, Sejarah Melayu; and the Suma Oriental. The latter by the Portuguese Tomé Pires. The chronicler described Melaka as having “no equal in the world.”

Some of the oldest surviving illustrations of what is now Malaysia appeared in Gordinho de Eredia’s Description of Malacca, Meridional India and Cathay (1613). De Eredia, born in Melaka in 1563, was the son of a Bugis princess and a Portuguese. His sketches include the first ‘realistic’ renderings of a Malay wearing a sarong with his ‘Crys’ tucked in his waistband, a boat, and a durian and mangosteen.

Another source for our imagination is from Chinese diplomatic and trading missions to Melaka. Named as the Wubeizi Chart, it serves as an illustrated map indicating tracks of vessels entering and departing the Melaka estuary, together with a stylized illustration of the hill overlooking the habour. The Chart mentions many other ports including Terengganu and its seaside hill as well as a number of east coast islands.

The Melaka Sultan’s palace and the great mosque was destroyed by the Portuguese. We can only see A Famosa the most illustrated structure of the Malay Peninsula of the 16th and 17th centuries. Drawn in naïve style, the earliest illustration dated 1515, depicts the fortress on the southern bank of Sungai Melaka, the covered bridge across it, the traders’ town on the opposite bank and the Strait of Melaka in front – according to Moore, “pictorial elements that would survive for centuries as the quintessential image of Melaka.”

Later, the Hikayat Abdullah (1849) describes the destruction of the fortress by the British in 1807, through Abdullah’s image, a picturesque but decaying town. And the early years of Malaysia’s visual history, the water colors and sketches depicting Pulau Pinang in the early 1800s were accurate albeit romanticized sources and historical documents. And lest we forget, the picture of the biggest deception in the nation’s history – the crime in the acquisition of Pulau Pinang. It is the well known engraving drawn by Elisha Trapaud inscribed as “View of the North Point of the Prince of Wale’s Island and the Ceremony of Christening it’ (1788). The ‘11 August 1786’ event never happened. There was no permission, nor treaty, nor signatures. The image was surreal.

Trapaud attempts at a realistic rendering, showing not only the British, but Malay structures – houses, and the hills of Bukit Bendera running through the centre of the island in the background, and what would probably be orchards in between. The spot was Tanjong Penaga. Trapaud’s engraving erased the town/port from the map. To rephrase Abdullah Munshi almost five decades later, “…a new world is created and all around us is change…” and distortion.

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.