Benua Melayu: Exploring another World View

THERE was a recent response forwarded via the social media critical of “Malay civilization.” Apparently it appeared to describe the previous Melaka Hari Ini column titled “Ideas on Civilizations: The Homeland Basis for Malaysia’s National Culture” (12 April 2021). Among other things, it had argued that the case for advocating Malay civilization through the social media and writings would often be accompanied by “a picture of Malay men doing silat…as if silat (and men) is what best represents Malay civilization.”

The illustration and visuals accompanying the writing is not the work of the writer, nor originating from the writer. It was the decision and authority of the newspaper concerned. I am not defending the work of journalism. But there are constraints and consciousness. At the same time, I would agree with the response of the writer on the problematic of representing Malay civilization.

Problems in representation persists in journalism and media – through headlines, texts, visuals, audio. It also is present in other forms of narrative and aesthetics, such as literature, art and architecture. Truth is, as popularly conceived, would always be the first casualty. No. On the contrary it is the morality in the reading of the narrative, and the interest inherent in the reader. And this is fused with the potential prejudice towards (new) theories, scholarship and perspectives, thus reinforcing the misrepresentation, altercating the discourse.

The title of this week’s column implies an extension of my two previous columns, one mentioned earlier and the other one being “Rantau and Merantau: Geography and Soul” (18 January 2021). In his 2007 work titled The Malay Civilization, Mohd. Aroff had described merantau as a trait of the wandering spirit of the Malays. With this specific trait in mind (although one can erroneously argue and equate this with migration), the Malays have been known to have become the first inhabitants of the island of Madagascar. This happened by about 600 AD.

According to Mohd Aroff, the date of settlement between was the year 0 to 400 AD. Linguistic studies found that Malagasi correlated with the Maanyan people of south eastern Borneo. More recent studies point out a genetic and linguistic linkage to the Banajarese in southern Borneo. This is an example of the merantau from Sundaland.

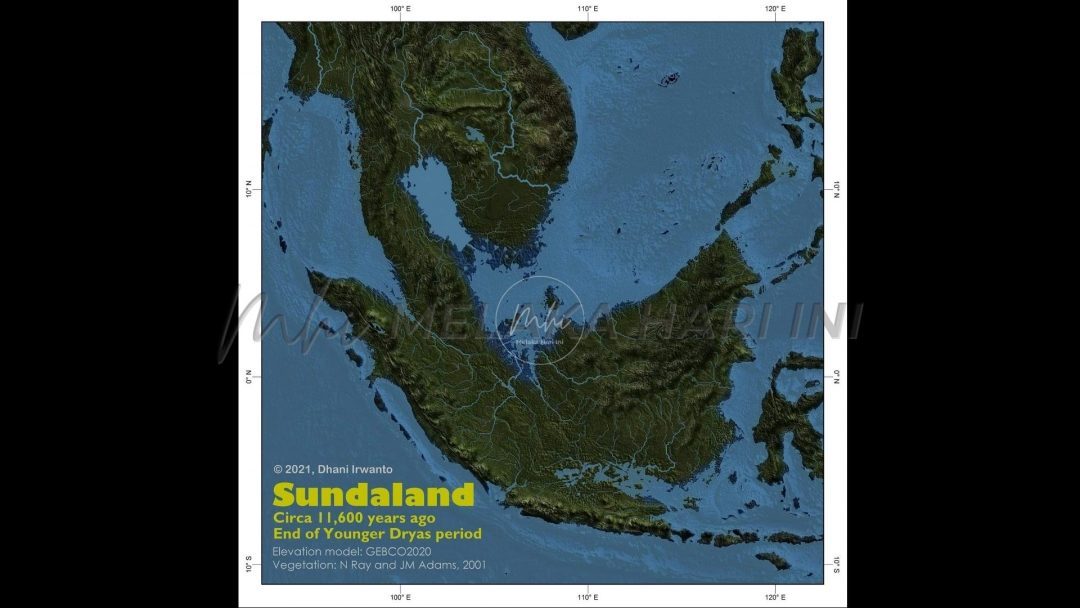

The “Out-of-Sundaland” theory was advocated by Stephen Oppenheimer, physician, geneticist and writer. In the 1990s, he had synthesized the various works from oceanography, archaeology, linguistics, social anthropology and human genetics. He placed the homeland of the Malays on the eastern seaboard of the now drowned Sundaland stretching from the northern tip of the island of Borneo to the present-day island of Banka in one area, and also from the south eastern coast of the island of Borneo, to the entire northern coast of the island of Java.

The Sundaland then, is the present-day Malay Archipelago, and the now-under-water Sunda shelf was a large sub-continental size land mass. The sunk lowland, now termed the Sunda Shelf is the world’s largest continental shelf. As dry land, it was mainly of low elevation with three very large river systems – one flowed northward , emptying into what we call now as the South China Sea, another flowed southeast-west ward into present-day Java sea, and another originating from Thailand, flowing into the Southeast China Sea. The tropical climate, abundance of rainfall made Sundaland an ideal ground for the development of human civilization.

The Sundaland perspective challenged the conventional appreciation of Asian History and Civilization which has always ascribed to the Chinese a lofty culture in the midst of an otherwise “barbaric” Asia. This view persisted for a long time. Later scholars realized the bias of Chinese sources. The sources would later develop a belief on self and others on who is civilized.

This is a relatively new understanding of the prehistory of the region. Oppenheimer in his book titled Eden in the East: The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia (1999) advances the view that Southeast Asia, specifically the drowned Sundaland, the last of the three “superfloods,” caused by the rise of sea levels about 8,000 years ago, was of the fabled Lost Atlantis. Generating much interest in recent decades, the Atlantis was Plato’s lost continent.

The drowned Sundaland was a vast plain of about 6,000,000 square kilometers in size, bigger than India, or about two thirds the of China. Oppenheimer argued that the peoples of Sundaland first started agriculture and was earliest in using stones to grind wild grains, as early as 24,000 years ago, 10,000 years earlier than ancient Eqypt.

It was further argued that some of the population in Sundaland had fled their homeland to fertilize other cultures. Some reached Africa and got into contact with the ancient Eqyptians. They related the story of the lost civilization to the Greeks. And that story was retold by Plato.

Much needs to be uncovered, through the fusion of many fields and disciplines. Certainly combining genetics and linguistics only are not enough. What is also important is that we do not dismiss such narratives as myths and fables.

The Bahasa Melayu word benua is Austronesian, with cognates across the Melayu-Polynesian world, as in the Maori whenua meaning “land” and “placenta”, Visayan “banwa and Rapa Nui “henua.” Benua is not merely land, nor continent. Benua is genesis and worldview – expressing geography, origins and deep history, expressing long term structures and causality.

Langganii saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.