Batak Newspapers in Colonial Sumatra: Tiger Sightings, bangso Batak and Narrating the ‘Modern’

Batak newspaper writing before World War II had deep, intertextual relationship with versions of the European novel. The newspapers inform us on modes of writing in school textbooks, guides to ‘old customs’, and ritual speech types found in chanted epics and oratory by chiefs. Batak novelists and newspapermen were prominent figures in colonial north Sumatra. They also spoke fluent Dutch.

Colonial Sumatra’s vernacular newspapers were lively cultural sites where one sees infusions of rhetorical forms and oratorical speech. It is the overlapping in narrating the modern with fiction – precisely in Benedict Anderson’s notion of imagined community. We find these in Angkola Batak-language texts.

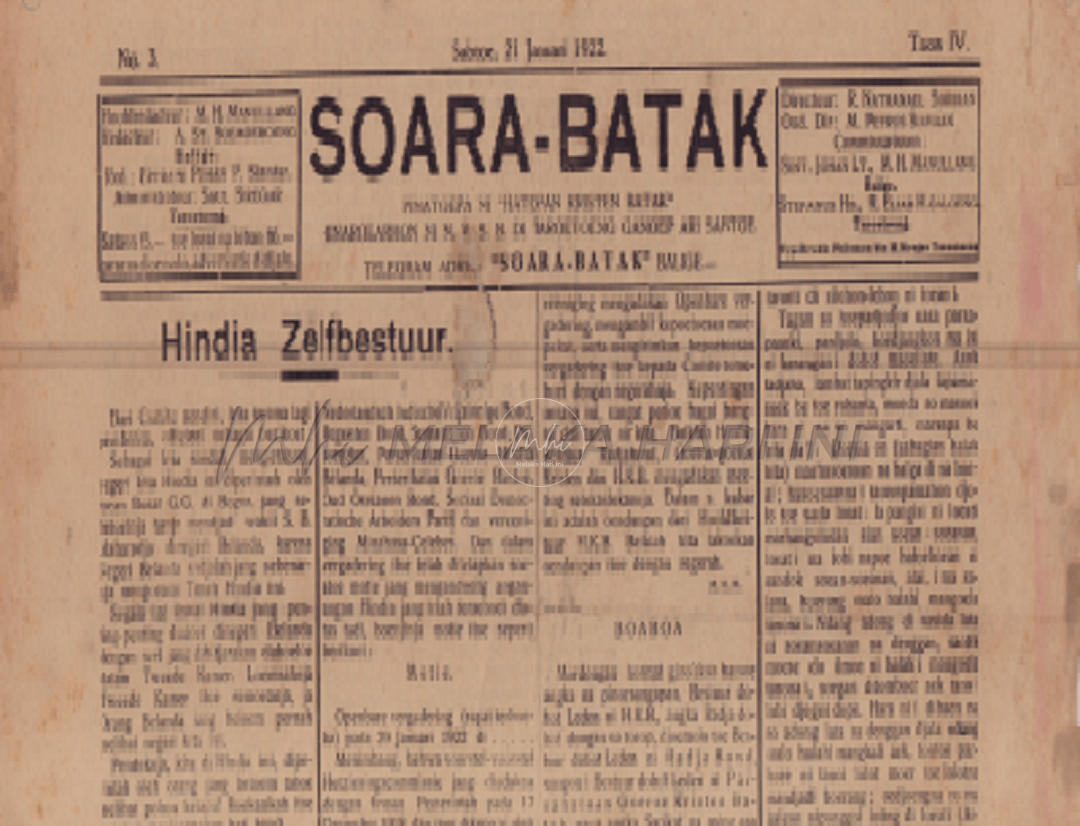

In her 2007 paper titled “Narrating ‘the Modern’: colonial-era southern Batak Journalism and Novelistic fiction as Overlapping Literary Forms” in the journal Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Journal of the Humanities and the Social Sciences of Southeast Asia) anthropologist Susan Rodgers explores Batak newspaper culture in the late colonial Dutch East Indies from 1910s to early 1930s. During the period, there was a thriving (if short-lived) Angkola and Mandailing Batak-language vernacular press issued by Batak-owned small printing presses in southern and central Tapanuli.

We can find these newspapers at the Perpustakaan Nasional (National Library) in Jakarta in its Katalog Surat Kabar (Wartini Santoso 1984). In north Sumatra, there is a large Batak press presence in Medan – in terms of the journalistic community, then and now. Also in my last visit to the Muzium Sumatra Utara at Jalan HM Joni in Medan 2018, and several visits over the last few decades, Batak manuscripts are prominently displayed. We would also encounter displays of Medan/north Sumatra-based newspapers, writers and journalists in their struggle for Indonesian independence.

The Batak-language newspapers is an example of the localization and indigenization of journalism and identity, not dissimilar to the Malay-language newspapers in the Peninsular before World War II. The Angkola and Mandailing society and journalists see the East Indies as a rapidly changing social universe anchored in the schools, the European plantations and Batak print culture – newspapers, novels and schoolbooks. Print literacy was indeed vibrant. The geographical locale of the east coast Deli was where the Bataks merged with modernity and their imagination of the world.

Such towns as Sibolga, Padangsidipuan, and Sipirok were small settlements. Some of the Batak-language newspapers were based in locales outside the highlands, in the Deli plantation belt of Pematang Siantar. With the establishment of plantation areas – tea, rubber and tobacco, and primary schools in the Angkola and Mandailing regions, instruction in reading and writing in the Batak syllabary (written characters/alphabets) was introduced.

According to Rodgers, the syllabary is a linguistic repertoire sometimes called the aksara These writing systems were similar to the Old Javanese script and may have been in use in the uplands for centuries. At European contact times the syllabaries were used to record laments, love songs, spells, and story cycles and tales. Some of these are displayed at the museum in Medan. I remember two on charms and spells, written on strips of bark formed into bark books known as pustahas. Sometimes these are folded concertina-fashion and furnished with beautifully-decorated wooden covers. And during the colonial period, Batak primary schools, called sikola metmet, literally ‘little schools’ introduced Batak children to surat Ulando (Dutch letters), hence the Latin alphabet.

The 1920s saw the emergence of “a heady southern Batak literary culture” (in print, Dutch letters) in Pematang Siantar, also in Sipirok, Padangsidimopuan, and Sibolga. This enabled the flourishing of Batak-language press for a brief period. From 1910s and continuing on through the mid 1930s, five predominantly southern-Batak-language newspapers appeared. The weeklies and biweeklies included Sipirok Pardomoean from Siporok, Tapian Naoeli and Poestaha from Sibolga. The period also saw the Batak-language Patoengkoan in Pematang Siantar, writing mostly about adat (custom).

News was locally defined. These are of clan celebrations, buffalo sacrifice feasts, school items, plantation crop prices, crime stories, tiger sightings, and family life features. There were also fillers on the Dutch monarchy, and countless essays on language matters – typically discussed in terms of being modern in the Indies. It was discovered that writers and journalists were often asked, What language (Angkola Batak? Malay? Dutch?) should the well-informed, newspaper-reading Batak household in Sipirok (or indeed in Deli), employ in raising small children?

Journalists and their readers of the Batak-language press were highly educated, with fluency in both Malay and Angkola Batak. From interviews conducted, Rodgers finds that the readers seem to have been a mix of schoolteacher families, coffee and cloth merchant elites, school-minded rajas, office clerks and hospital clinic staff.

By the 1930s, the Batak press coverage included stories on political clubs, the world depression, nationalism in other Asian countries, and political parties in the Indies. There were also newspapers that used Malay, namely in Tapanuli. The titles include Sinar Merdeka and Soera Sini from Padangsidimpuan; Soera Ra’jat and Pardomoean from Sipirok (the latter mixed with Angkola Batak), and Bergerak and Hindia Sepakat from Sibolga.

In the heydays of the Batak vernacular press, issues of being maju, ‘progressive, forward thinking’ were discussed as early as 1914. A front-page story from the 8 January edition of Poestaha of that year was headlined ‘Sai madjoe nian bangso Batak!’ (May the Batak people indeed always go forward!). Becoming maju was a subtler trope in the Batak-language fiction of the 1920s. On the other hand, we also find consistent critiques of Batak ‘backwardness.’

#####

Langgani saluran Telegram kami untuk dapatkan berita-berita yang terkini.