Of Nutmegs and Cloves: European Pirates in the Archipelago

THE Banda islands, in the province of Maluku, in the easternmost part of the Malay Archipelago were famous for nutmegs. It was for the Spices (and the Gospel) that led the Europeans to traverse the Indian Ocean. They said it was also for the pepper. The king of spices will be the ingredient for another story. For now, we follow an English ship to the nutmeg growing Banda islands.

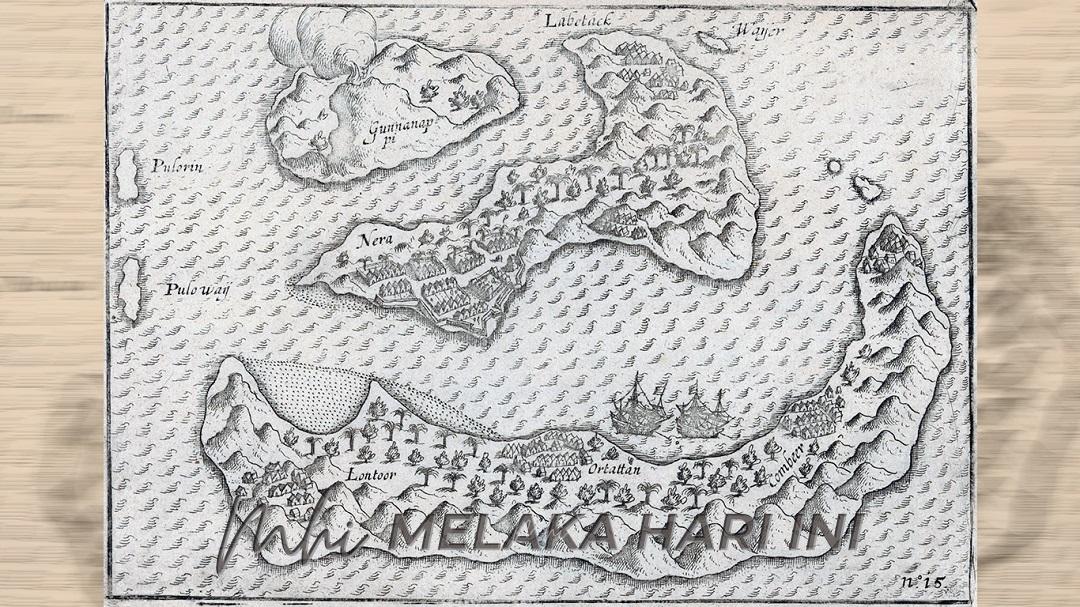

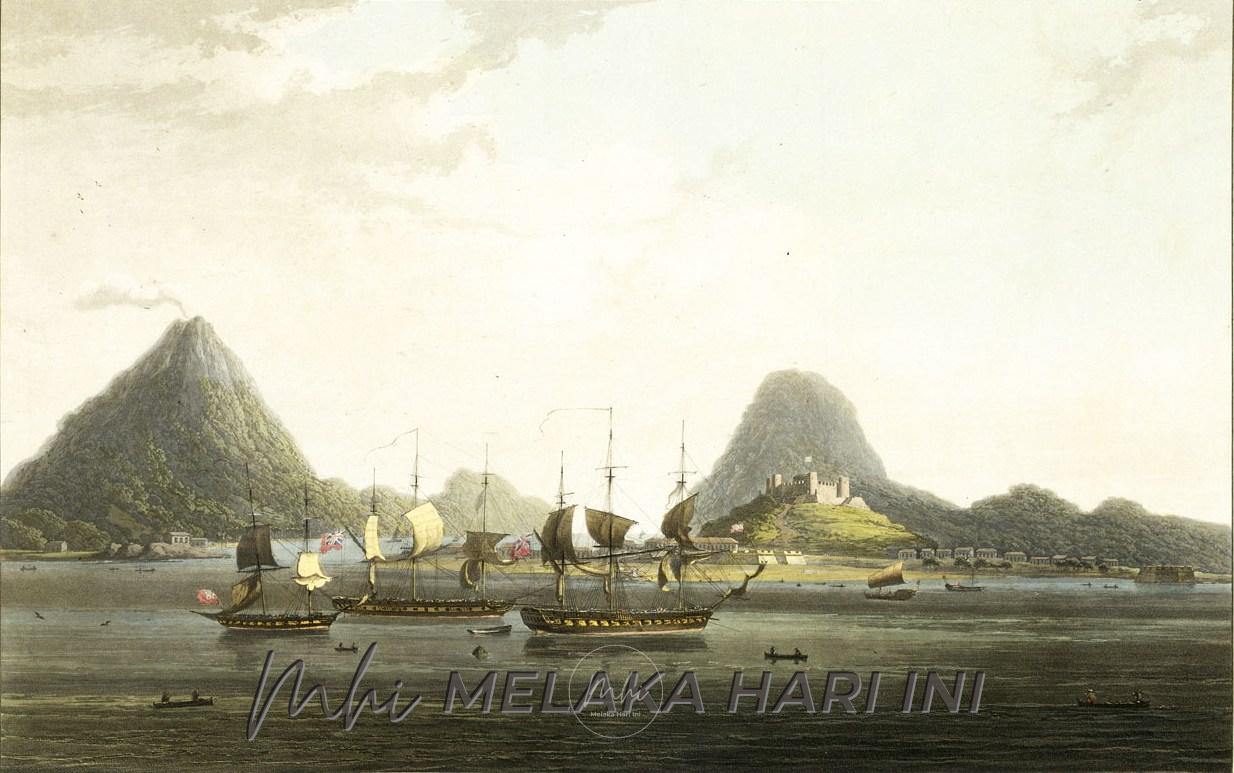

When the ship arrived at the main island of Neira, it found that the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had set up shop, and had forcibly imposed a monopoly on the locals. Faced with Dutch hostility, the English decided to trade with two tiny outlying islands – Pulau Ai and Pulau Run – where the locals had resisted Dutch pressure.

Pulau Run was a mere 700 acre of nutmeg plantation. It did not even have enough water or rice to sustain its small population. The story has it that the local chiefs were so afraid of the VOC that they threw themselves under English protection. Thus Ai and Run became the first colonies of the English East India Company (EIC). That would be the first property of the Company, dubbed the world’s first global corporate raiders. That was in 1610. Many would have erroneously thought it the first British colony in the Malay Archipelago was Pulau Pinang.

The colonisation of the islands was said to be “a measure of the commercial importance attached that King James I would proudly proclaim himself “King of England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Puloway and Puloroon.” as retold in Sanjeev Sanyal’s The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History (2016). The notoriously cruel Dutch governor general, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, mentioned in our school textbooks, led a genocide. He massacred the population at Banda whom he accused of violating the VOC monopoly. Of the 15,000 people on the island, barely a thousand survived death or deportation. The VOC attack on Banda was one of the darkest episodes in the history of Dutch colonialism. It was a plunder on civilized society, law and order. Banda’s 48 Orang Kaya were beheaded. Some 789 family members of the Orang Kaya were also put to death by beheading. According to historian Bondan Kanumoyoso from the University of Indonesia, the executions were served by the Japanese Ronin.

Those who survived were transported by ship to Batavia, some placed outside the city walls, made into slaves, and others sent to Ceylon. Coen then turned to Pulau Run. Five hundred VOC soldiers landed on the island. That spelt the end of the EIC’s first colony. Sanyal pointed out that Coen would continue to systematically tighten his control over the East Indies by using brutal tactics to terrorise both European rivals and the local population.

In 1624, he used trumped up charges against the 15 Englishmen based in Ambon, also in the Maluku islands. Some of us may remember it as the Ambon Massacre. Almost 20 years later in 1641, the rivalry among the European pirates saw the eviction of the Portuguese from Melaka. Thus the Dutch managed to secure control over the routes to the Spice islands.

For the VOC, their full monopoly was to be sealed through the Treaty of Breda signed on 31 July, 1667 between the Dutch Republic, and its allies, France and Denmark on one side, and the British monarchy on the other. The rivalry in Europe was brought into the Malay Archipelago. The territorial compromises were arrived at thousands of kilometres from their European homeland.

The Treaty was in exchange for the Pulau Run, and Suriname in South America. The island and Suriname were to be given to the Dutch. The British got the Dutch colony of Nieuw Amsterdam in North America, renamed New York. Meanwhile more suffering was in store for the Banda Islands. Kanumoyoso in his paper “Banda Islands and the Treaty of Breda 1667” (2020), described how the Dutch wanted to maximise the island’s nutmeg production. The VOC used slaves as workers to grow, cultivate and harvest nutmegs.

The purchase price of VOC nutmegs in Banda was well below the selling price in Amsterdam. The profit margin could be as high as 1000 per cent. The staggering profit to the VOC became the main source of dispute between the Dutch and the owners of the plots – each plot approximately 3000 square meters.

The Banda islands and the competition on the nutmeg trade is a classic example of European barbarism in the world. But our history has not interpreted it that way. In the beginning, there was no monopoly, no violence, no genocide, and no slavery. The Portuguese was in Banda 1512, one year after they ransacked and pillaged Melaka. The Portuguese pirates were the earliest to monopolize the nutmeg trade. They were there too to avenge the defeat of the Franks to the Muslims during the Crusades, and to make Portugal a powerful Christian nation.

Then, the Dutch arrived in 1599, at the time when the Banda peoples were trying to free themselves from the Portuguese. The arrival of the Dutch was warmly welcomed. It was false hope. They cannot rely on pirates; or “country traders” in disguise through private trade formalized by the different European monarchs granting commissions. These were legalized privateering, represented and narrated in Eurocentric historiography as such. Reversing the narrative is long overdue. We read how the locals have been (re)invented as pirates in their own land (and seas), by the very pirates who stole the nutmegs.

NEXT WEEK : The Company

Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican is Professor of Social and Intellectual History with the International Institute of Islamic Tho ught and Civilization, International Islamic University (ISTACIIUM). He is a Senior Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research Centre and Hub at De La Salle University, Manila, the Philippines.