A Kedah Island: the stolen past of Pulau Pinang

THE story of this island of Kedah is contested. The Eurocentric narrative accords Francis Light the founding status of Pulau Pinang in 1786. This has alienated another perspective. Revisiting the history of the earliest communities who inhabited this island of Kedah before 1786 remains an imperative role for the writing of Malaysian history. It must be remembered and be reminded that the history of Pulau Pinang did not begin from 1786. That year is a myth.

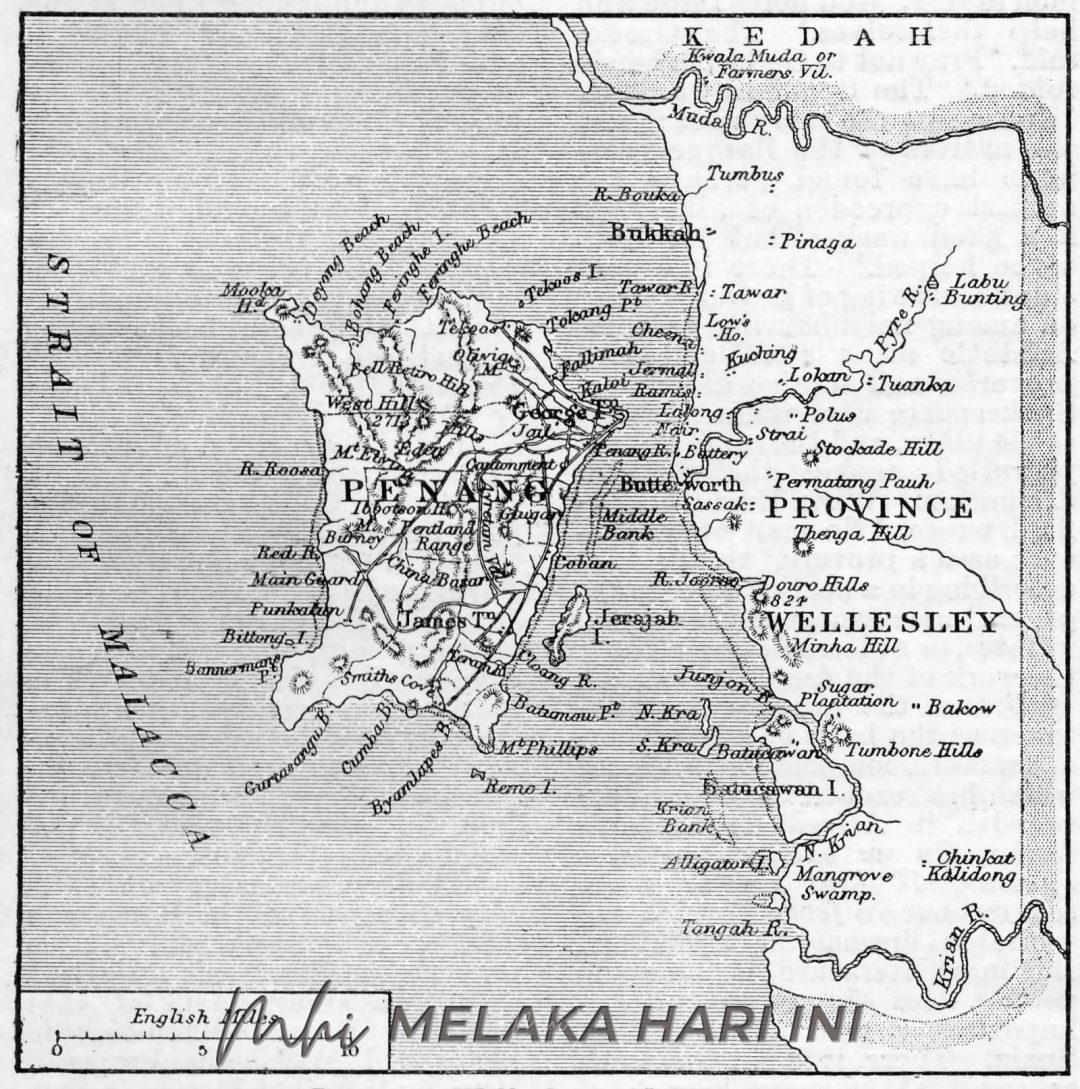

The Malay narrative is forgotten. James Low in 1849 in translating the Merong Mahawangsa (The British calls it the Kedah Annals), emphasized “It is a History of Keddah on the Malayan Peninsula; and, independently of any intrinsic value which it may possess, it is interesting to the British, since the settlement of Penang and Province Wellesley once formed an integral portion of the country of Keddah (The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, vol.3, no.1, January 1849).

The narrative of Pulau Pinang, together with Kedah, needs revisiting, rewriting and decolonizing. The island was believed and judged to be terra nullius (literally ‘nobody’s land’), although that belief seems to be apparently fading over the years. This is the template constructing the history of Malaysia too – from the school textbook to public history. Malaysian school history and public history unfortunately differ, and may also contradict.

Pulau Pinang is of course, not alone. Parallels are seen with the history and historiography of Singapura. Circumstances are different. Yet Pulau Pinang is as history-starved as her counterpart down south. I have used the term “pengemis sejarah” (beggars of history) in my work on Batu Uban: Sejarah Awal Pulau Pinang (2015). There is a stoic absence, an emptiness, on the island’s past, both by default, and by design.

Pulau Pinang’s past destiny echoes that of what historian K.G. Tregonning’s declaration that “Modern Singapore began in 1819. Nothing that occurred prior to this has particular relevance to an understanding of the contemporary scene; it is of an antiquarian interest only”.

Tregonning, Raffles Professor of History at the University of Singapore, made the declaration to a volume commemorating the 150th anniversary of Raffles in Singapore. The Tregonning remarks represented the prevailing ideology held by historians of Singapore’s past in recent times. This is the template, not only Singapura history, but that of Pulau Pinang, the rest of Malaysia, and the region. It has been argued that nothing very much appeared to have happened in Singapore before Raffles landed.

The history of Pulau Pinang has been framed as a positive outcome of British colonialism. Francis Light as ‘founder of Penang? Or the founder of the Port of Penang? Fact, or myth? To accept that the template as a fact of history itself falsifies the past. To be sure there are many roads to the past. The historical narrative is also an argument. Colonial archives are certainly biased. And the Arkib Negara Malaysia has remained as such. Do a word search on ‘Masjid Jamek Batu Uban’ /or ‘masjid Pulau Pinang,’ and one finds the line “Masjid Melayu Lebuh Aceh dianggap sebagai masjid yang tertua di Pulau Pinang” (The Lebuh Aceh Mosque is considered the oldest mosque in Pulau Pinang). That is a colonial narrative.

The colonial template is embedded in our historians, custodians of heritage and policy makers. For example, Francis Light’s statue is still displayed in its splendor (marred by the red paint vandalism early 2020). And what is Frank Athelstane Swettenham’s statue doing on the grounds of Muzium Negara in Kuala Lumpur? And the bust of King Edward VII in the same location? And this is coming to 64 years of political independence. Colonialism is never benign.

What happened in 1786 is the illegal occupation of Pulau Pinang. It is plunder and vandalism. The colonial past is silent on its own criminality. Light did not commit murder. Stamford Raffles did. It is the criminality of the colonial state. Should the Sultanate of Kedah, and the people Kedah and Pulau Pinang demand a public apology, and reparation from the British for distorting history, and identity? Opening a new chapter in the nation’s history renders the old narrative “dibuang habiskan” (stealing a phrase from Raffles on the Palembang Massacre).

Another story goes that the Sultan of Kedah gave his daughter; or was it a lady from the Kedah court in marriage to Francis Light and offered Pulau Pinang as a dowry, in return of protection by the English East India Company (EIC) against his enemies.

The Sultan of Kedah, Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah claimed that he was merely allowing the British, on certain conditions, to occupy the island while taking care of the Sultan and his Kingdom against his enemies, especially Siam. There was no agreement, no treaty of 1786. Pulau Pinang was never given away. Kedah history needs a revision.