The Tanah Air has always been cosmopolitan

THE Malays have two sets of narratives in encounters with the West – one is actual, the other mythical/ metaphysical. Melaka was one of the earliest places of encounters, in both sense of the word, producing the Ferringhis and Rum (Rome).

These are popular conceptions of the world, forging our consciousness as a nation. And so when the Ferringghis arrived at the shores of Melaka, in less than civilized ways, the sight was familiar. So also with the Belanda. The Melakans and Malays were used to seeing a wide assortment of people. The Europeans to them was just another aspect of that diversity.

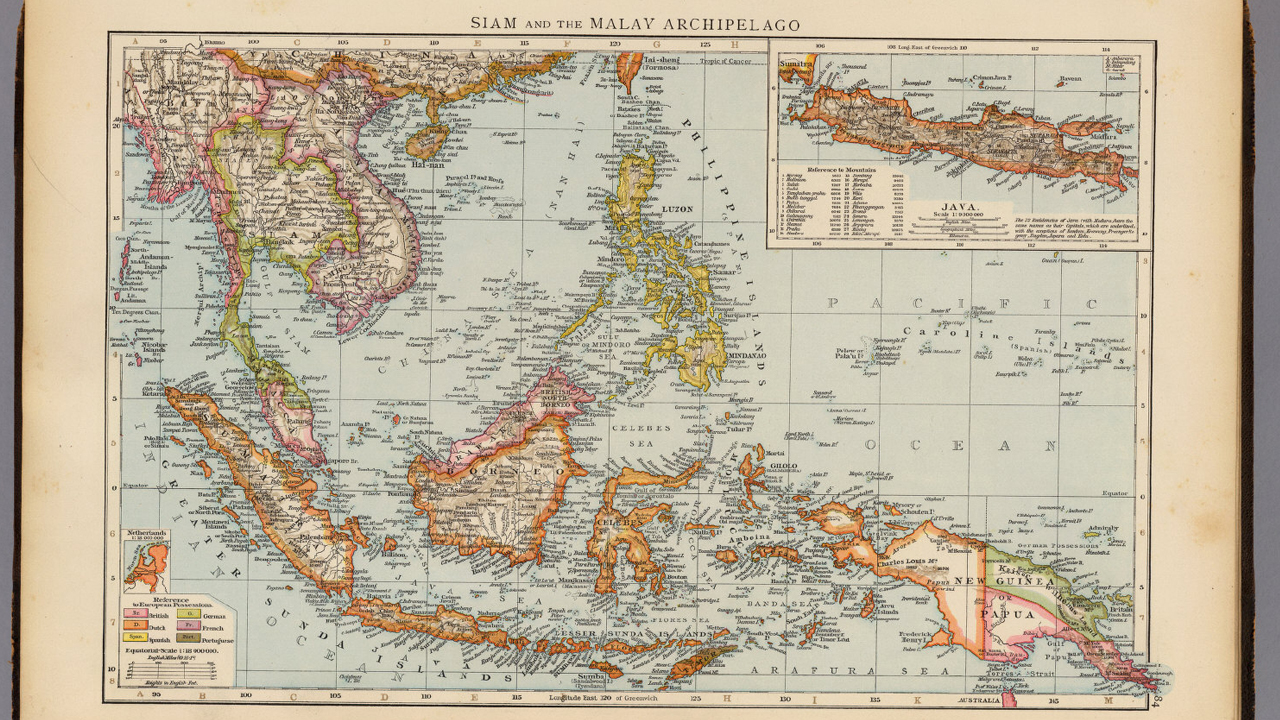

The area of land and water where the winds meet – the geographical markers of ‘atas angin’ (above the wind) and ‘bawah angin’ (below the wind) have always evoke the cosmopolitan nature of the Tanah Air.

Destined by geography, this part of the world has become the world’ biggest and most important archipelago.

The Tanah Air brings together a continuing narrative evoked by maritime and cultural crossroads from much earlier on. The Tanah Air is a larger than life concept.

There is a common history, deep linguistic and cultural roots, and a general awareness of the role of the sea that brings peoples from both the lands above the wind, and the lands below the wind. In recent times, there is a new wave in the Malay narrative on the archipelago.

Not only from the inside, but also from observers external to the Nusantaria, as Philip Bowring describes the rantau in his 2019 book Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia’ Great Archipelago.

To the former journalist, Cambridge University history graduate and student of the history and economy of maritime Asia, Nusantaria expresses the larger region of the Archipelago, not only confined to Nusantara, as commonly understood to refer to what is now the Indonesia islands.

Bowring was a familiar figure in Kuala Lumpur in the 1980s, writing about Malaysia and the region in his International Herald Tribune column.

I was then a cadet reporter with Bernama, the Malaysian National News Agency. He uses ‘Nusantaria’ to denote a broader zone, the single maritime region between the northern entrance to the Melaka and Luzon straits, and the Banda islands in the extreme east of the archipelago. The narrative on the Tanah Air, while predominantly describing the Malay world, also touches Taiwan and Madagascar, the coastal Thai, Chinese, Tamil and other players in the history of the exchange of goods, peoples and ideas both within the region and with peoples to the west and north-east.

Bowring also notes Nusantari’s correspondence to the term ‘Nusantao’ used by the archeologist of Southeast Asia, Wilhelm Solheim. Nusantao refers to the mostly Austronesian speaking peoples of the ancient trading networks of the islands and coasts, where tao means people in many Austronesia languages.

Many other terms were used by various powers and civilizations. These included the Japanese term ‘Tonan Ajiya’ which means ‘South East Asia,’ (used from the late nineteenth century) Cham Sea, Malay Sea, and the Spice Sea.

The China seas only came into Western use around 1800. ‘South’ was added in the early twentieth century. To the Chinese, the region was the ‘Nanyang’, meaning the South Seas.

Nevertheless, this region’s history is poorly known, more so from within. The Tanah Air was once a connected whole, with a collective memory and a common history. But post colonial states prefer their own identities, where history begins from the moment past midnight of the year of their political liberation.

The past is ignored. Cultures and cosmologies regressed. Identities remain hidden, fragmented or lost. History remains the poor soul of the Tanah Air.

Geography is lost to Google. Austronesia becomes a meaningless word, notwithstanding it is the first instance of a linguistic marker with shared genetics and cultural characteristics.

The Melaka strait was central. Before Melaka, there was Srivijaya, and Kedah and many more. The foreign traffic made the ports cosmopolitan. Melaka’ 84 languages were preceded by what was written in Arabic five centuries earlier – that even the parrots in Palembang could speak many languages including Arabic, Persian and Greek.

*Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican is a Professor of Social and Intellectual History with the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, International Islamic University (ISTACIIUM). He is a Senior Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research and shun (SEARCH) at the De La Salle University, Manila, the Philippines