Ibrahim Yaacob writing against imperialism

PROF. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican

IBRAHIM Yaacob’s 1941 Melihat Tanah Air is a futurist document of the nation. To him, the Malay Archipelago’s location then described as the east (dunia timur) holds the key to the Pacific Ocean and the world economy.

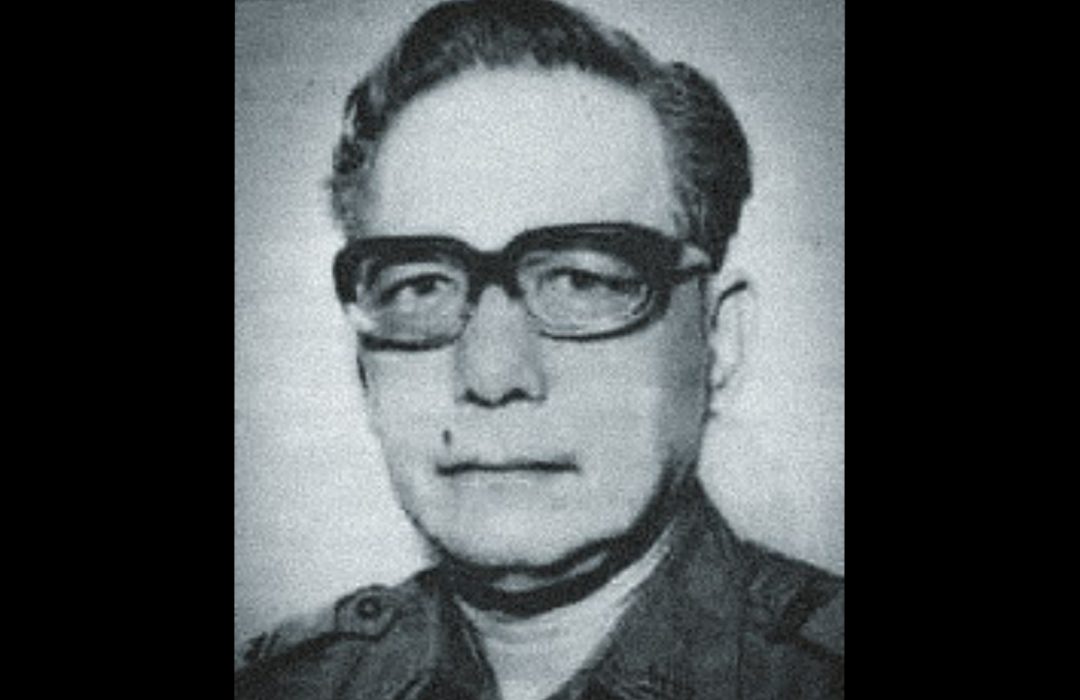

Ibrahim has managed to strategise and provide foresight for the Malays under colonial conditions before World War II. He repeatedly emphasized the significance of the Alam Melayu, especially Malaya to world power. Melihat Tanah Air is not a history book. It renders the past and the future as Ibrahim (1911-1979) saw it.

Ibrahim was an opponent of the British colonial government, and president and founder of the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) in 1938. Born in 1911, Temerloh, he joined the Sultan Idris Teachers’ Training College (SITC) in 1929 and graduated two years later as a teacher. His Tanjong Malim experience gave him access to a range of European ideas and doctrines including that of anti-colonialism.

During the 1930s, he wrote a series of articles critical of the British to the Malay newspapers. Anti-colonial sentiments and movements across the Strait of Melaka sought him to reproduce it in Malaya. Indonesian periodicals such as Fikiran Rakjat, published in Bandung about 1928, inspired the man.

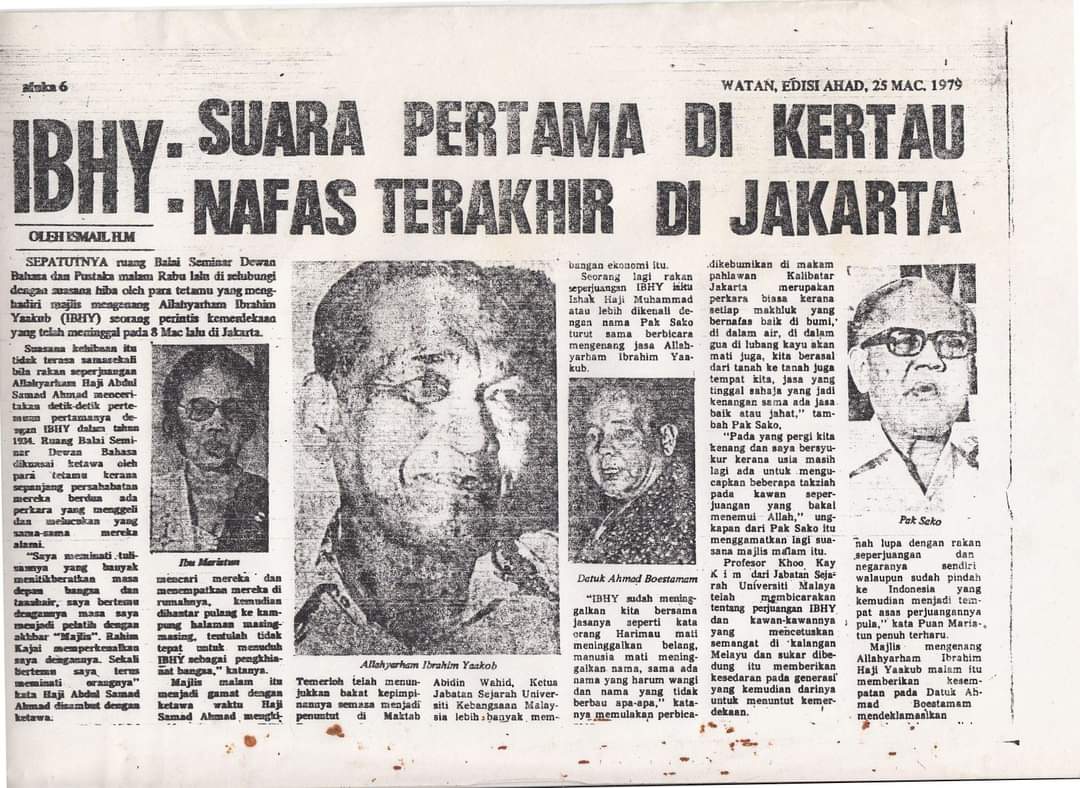

Nationalist and writer, popularly known as Pak Sako, whose name is Ishak Haji Muhammad, in his foreword to Melihat Tanah Air described that it was in Tanjong Malim that the seeds of national awareness (kesedaran nasional) was imbued in Ibrahim. Ishak’s Foreword evoked a consciousness against the “white man” (orang kulit putih), as the cause of the downfall of the Bangsa Melayu.

The mood of the times in the 1920s and 1930s was consciousness and loyalty to kaum (people/family/group), bangsa (race) and watan or tanah air (homeland), not necessarily negara (country) and agama (religion). Concepts of race and ethnicity as legacies of British colonialism provides much insight on Ibrahim’s worldview. His writings engender a transition from ‘their’ history to ‘our’ history. In Ibrahim, we see a product of Colonial education, reconstructing Malay nationhood.

Ibrahim was well aware of the role of newspapers. Ibrahim served as one of the editors of Majlis, one of the few prominent Malay metropolitan newspapers based in Kuala Lumpur in 1938, the same year he formed KMM. Ibrahim became the editor of Majlis at about November 1939 and continued there until late in 1941.

KMM’s dream was for a Melayu-Raya (Greater Malaya). He pioneered a broader geo-cultural entity. The Malay-Archipelago, or the Malay-Nusantara rantau – in his vision as a polity, is where her future lies.

A reprint in rumi of Melihat Tanahair was issued by Percetakan Timur in Kuantan in 1975. He was 31 years old when Melihat Tanahair first appeared. Ibrahim travelled throughout the peninsula. He provided two reasons behind his travels throughout the Malay peninsula for one year between 1940 through 1941.

The first was to mobilize the consciousness of the Malay race (menggerakkan kesedaran bangsa Melayu) to instill a sense of national unity (perpaduan bangsa) amongst the Malays in Peninsular Malaya. His efforts were in his capacity as the president of the Young Malays Union – Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM).

The second reason stated was to research on Malay economic life and affairs which according to him was “extremely neglected by the English colonialists” (Untuk menyiasat hal ehwal kehidupan iktisad [ekonomi] orangMelayu seluruhnya yang terbiar terlantar oleh penjajah Inggeris…). Ibrahim was aware that his destiny was the prison. He noted that the second part of the manuscript was confiscated by the police when they arrested him.

In his travels, he refuted the lazy native myth, of which 30 years later was to be articulated by scholar and public intellectual Professor Syed Hussein Alatas. Ibrahim’s rationality is that of the European Enlightenment. He purveyed foreign ideas, at the same time regretting the Western and capitalist intrusion into “the pristine world of the Malays.”

It is obvious that bangsa consciousness dominates Ibrahim’s writings. He addressed the first chapter as “My People: Peninsular Sons of the Soil” (Orang-orang Saya Bumi Putera Semenanjung). It evokes his emotional resonance on nation and identity. Ibrahim was indeed creating a single ethnicity of the Malays; not wanting to see conditions leading to fragmentation (he used the term bercempera), without direction, or a national belief. He also spoke of national rights (hak kewatanan). His kewatanan conveys the notion of “national”, and of “homeland” (tanah air), concepts worth investing for the future.

The pride of race in Ibrahim saw the spread of European ideas of the “Fatherland”, strongly echoing the patrie in Montesquieu and Rosseau, thus connecting the Malay thinking on bangsa, tanah air and merdeka, to that of Europe. European ideas, mainly through Indonesia, and Singapura, have attracted him to carve a nation, to liberate his bangsa from colonial geography, and eventually forming a pan-Malay state.

Prof. Dato’ Dr. Ahmad Murad Merican is Professor of Social and Intellectual History with the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, International Islamic University (ISTACIIUM). He is a Senior Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research Centre and Hub at De La Salle University, Manila, the Philippines.